Part 1

Unpublished Manuscript

DO NOT DISTRIBUTE

See published version:

Metzger, M. , and Fleetwood, E. (2010). Cued language: What deaf native cuers perceive of Cued Speech. In C. LaSasso , K. Crain , & J. Leybaert (Eds.), Cued Speech and cued language for deaf and hard of hearing children (pp. 53-66). San Diego, CA: Plural.

Abstract

The primary purpose of this study was to determine whether cued messages are products of a different set of distinctive features than are spoken messages. Toward that end, this study compares the linguistic information received by a control group of hearing native speakers of American English with the linguistic information received by a group of deaf native cuers of American English where such information is simultaneously spoken and cued to both groups. Some test material was designed to coincide linguistically across mode (i.e. spoken, cued). Some test material was designed to differ linguistically across mode.

As predicted, (a) responses were consistent within each group for all items tested, (b) responses were consistent across groups where simultaneously cued and spoken test material was designed to coincide linguistically across mode and, (c) responses differed across groups where simultaneously cued and spoken test material was designed to differ linguistically across mode. Because responses were group consistent for all test material, it can be said that each of the cued mode and the spoken mode are systematic and sufficient for conveying linguistic information. Because responses differed across modes for test items designed to differ linguistically across mode, it can be said that mode-specific attributes identify the linguistic value of a given message. Finally, and to the point of the current study question, because the value of particular linguistic messages differed across groups even when group-internal agreement existed, it can be said that mode-specific attributes characteristic of speech are not entailed by the attributes that characterize cued messages.

Findings provide evidence that the distinctive features of speech are not phonetically relevant to receiving, processing, and comprehending cued messages. Findings leave open the possibility that acoustic (i.e., spoken) information that might accompany cueing could be used redundantly or confoundedly in receiving and comprehending linguistic information. Such a possibility is analogous to that of the function and influence of visual information as used by the hearing speakers of a given language: the information is neither primary nor compulsory in nature. Findings help to distinguish between the systematic or definitional requisites of cueing and the variables characteristic of those who send (e.g., some speak while cueing) and receive (e.g., hearing acuity varies) cued messages.

Findings support the use of cueing with and by deaf individuals who (a) do not acquire language primarily through hearing and/or (b) who do not primarily use speech to communicate language. Findings also support the use of cueing with deaf individuals who use at least some hearing and/or speech to acquire and/or communicate language.

Does Cued Speech Entail Speech?

An Analysis of Cued and Spoken Information in Terms of Distinctive Features By Earl Fleetwood, M.A. and Melanie Metzger, Ph.D.

Cued Speech (Cornett, 1967) is an articulatory system1 designed to support the development of literacy skills in individuals who are deaf/hard-of-hearing. “The development of Cued Speech came about specifically because of concern over the fact that deaf children do not typically learn to read well” (Cornett & Daisey, 2001, p. 256).

The role of Cued Speech in the development of literacy skills is based on the notion that it conveys all of the linguistic structures of a traditionally spoken language beginning at the phonemic level. By design, Cued Speech uses hand shapes paired with mouth shapes to represent consonant phonemes and hand placements paired with mouth shapes to represent vowel phonemes. These visible representations of the phoneme stream provide for the formation of syllables and words and subsequently carry the grammar of a given consonant-vowel language.

Cued Speech is designed with the idea that through sufficient exposure to a language that is cued in natural interaction, individuals who are deaf or hard-of-hearing will acquire the phonology, morphology, and syntax of that language. Because natural language acquisition occurs passively through consistent exposure to natural language use, it would follow that deaf/hard-of-hearing cuers need not consciously ponder this phonologic, morphologic, and syntactic information any more than do individuals who use signed languages and spoken languages. Practically speaking, exposure to a cued language2 used in natural interaction serves as a linguistic avenue for (a) gaining world knowledge, (b) learning how that language is used in face-to-face interaction, and (c) subconsciously acquiring the phonologic, morphologic, and syntactic structures of that language.

The deaf/hard-of-hearing individual who internalizes the phonology of a cued language, such as cued Amerrican English, can apply that information to the process of reading.

Orthographic representation of consonant-vowel phonology (i.e., written characters of the alphabet) can be correlated with the internalized cued phonologic representations. The deaf/hard-of-hearing individual can then become an autonomous reader, utilizing phonologic word attack strategies to decode written words (Alegría, Lechat, & Leybaert, 1988; Leybaert, 1993), and world knowledge, gained through language used in natural interaction, to understand what is read.

Evidence that cueing has positive effects on literacy development has been found in numerous studies (see Leybaert & Charlier, 1996 for a review). For example, Leybaert (1998) suggests that deaf native cuers develop phonological representations of a given language comparable to hearing native speakers of that language. In fact, Cued Speech appears to provide linguistic information sufficient for deaf cuers to develop literacy skills on a par with hearing speakers of that language (Alegría, Dejean, Capouillez, & Leybaert, 1990; Alegría et al. 1988; Leybaert & Charlier, 1996; Wandell, 1989).

Unfortunately, discussion in the literature has left the distinction between phonetic and phonemic information ambiguous where the functional requisites of cueing are concerned. As a result, attributes that serve to define the nature of cued input have been neither clearly nor consistently characterized. This is particularly significant when it comes to identifying the distinctive features that comprise cued phonological segments. Because, speaking and cueing are so phonetically and phonemically intertwined in the literature, questions remain about the necessity of speech knowledge and speech production skills in the production, reception, perception, and processing of cued messages. Because the nature of phonologic segments is foundational in a linguistic sense, answers to such questions have significance with regard to both how cueing functions modally and with whom it can best be used.

The issue of language modality has received increasing attention in recent years. After several decades of finding evidence that signed languages are as linguistically legitimate as spoken ones, researchers have begun to turn their attention toward the unique distinctions between languages commonly found in the visual mode and languages commonly found in the acoustic mode (see, for example, Hildebrandt and Corina, 2000 and Channon 2000 regarding phonology, Mathur 2000 and Wood and Wilbur 2000 regarding morphology, McBurney 2000 and Pfau 2000 regarding syntax, and Grote 2000 regarding modality effects on the mental lexicon, and Lucas and Valli 1992, Lucas et al 2001 regarding sociolinguistic variation).

Research and discussion have also contributed to a better of understanding of the distinction between modality, communication systems, and language. For example, some have examined the impact of manually-coded English signing systems on the acquisition of English grammar (at least morphologically and syntactically) through the signed modality (see Bellugi, Fischer, & Newkirk, 1979; Davidson, Newport, & Supalla, 1996; Kluwin, 1981; Marmor & Petitto, 1979; Maxwell, 1983, 1987; Schick & Moeller, 1992; Stack, 1996; Supalla, 1990,1991). Others have examined attempts to convey English grammar (phonologically, morphologically, and syntactically) through the cued modality, with cued languages such as cued English and cued French (cf Fleetwood & Metzger, 1991, 1998; LaSasso & Metzger, 1998). Recent literature also specifically compares and contrasts the cued modality with the spoken one (cf Fleetwood & Metzger, 1998; Leybaert, 1993; Leybaert & Charlier, 1996; Leybaert, 1998; Leybaert, Alegria, Hage, & Charlier, 1998).

Such lines of study consistently indicate that the mode of communication does have an impact on the efficacy of the associated method of communication. For example, even when manually-coded English sign systems serve as primary input to deaf children and youth, their signed output is more likely to incorporate the reduplication convention of natural signed languages to encode the notion of “plural” than to use the affixation convention of English (Supalla, 1991). Additional distinctions can be found at the phonological, morphological, and syntactic levels of linguistic structure. Thus, the visual-spatial modality encodes information about English differently than that encoded in the acoustic mode.

Conversely, a case has been made that Cued Speech is able to visually encode information about languages that are traditionally conveyed acoustically. Research (Hage, Alegria, & Périer, 1990; Kipila, 1985; Metzger, 1994; Mohay, 1983; Moseley, Williams-Scott, & Anthony, 1991; Nash, 1973) provides evidence that deaf children consistently exposed to a cued language from an early age naturally acquire salient phonologic, morphologic, and syntactic features of that language. Those same features consistently elude deaf children who grow up signing a natural language, a signed system, or who are raised with oral methods (see Leybaert, 1998; and Leybaert & Charlier, 1996 for overviews of this discussion as it pertains to literacy development). Nevertheless, in research and discussions about Cued Speech, confusion seems to persist regarding the mode of communication.

Cued Speech as it is described and defined in the literature is a bimodal system, visible and acoustic by nature. In light of findings regarding the relationship between auditory and visual information in hearing people, the notion of using information in multiple channels is not surprising (see Summerfield, 1987 and Schwartz, Robert-Ribes, & Escudier, 1998 for an overview of audio-visual fusion and speech perception). However, the quantity and quality of the acoustic information perceived by deaf individuals is not as predictable or controllable. Thus, a question for the current study is, “Is acoustic information necessary to the efficacy of cueing a language?”

The question of whether Cued Speech functions as a bimodal system, as a visual system with optional acoustic redundancy, or simply as a visual system is an interesting theoretical issue. Perhaps more importantly it is also a practical one. Practically speaking, the notion that Cued Speech functions as a bimodal system is fundamental to perceptions and resulting decisions regarding the linguistic and communicative competence of deaf cuers. This becomes clear where, for instance, Perigoe and LeBlanc (1994) discuss the development of speech production in “the hearing-impaired child.” Toward this end they say, “One must concentrate on making the spoken language output of the hearing-impaired child as clear as his/her spoken language input” (p. 30). A fundamental assumption entailed by their statement is that the child’s linguistic input is via access to a spoken language and, hence, the articulation of speech. One purpose of the current study is to examine the validity of that assumption. Is it accurate to conclude that spoken language is the form of input carried by a cued message? If it is not, then perhaps “the spoken language output of the hearing-impaired child” is in fact “as clear as his/her spoken language input.”

The term spoken is the operative consideration here. Perhaps a reason that a deaf cuer might be found in speech therapy is that Cued Speech does not provide spoken language input. Maybe the reason “it is difficult to tell a child he is incorrect when expressively both his language and cues may be perfect” (Perigoe & LeBlanc, 1994, p. 31) is because the child’s output is, in reality, a “perfect” reflection of his/her input. Perhaps it is not the child who is “incorrect” but, instead, the accuracy of definitions against which his/her performance are being measured. This notion is addressed by the current study.

Other discussions of Cued Speech are also based on the idea that it conveys spoken language. According to Daisey (1987), Cued Speech provides “an internalized speech-coding system and enables a deaf child to have spoken English–that is, syllabic-phonemic English–as his native language” (p. 27). This statement reflects inconsistency with regard to what Cued Speech codes: Does it code speech (e.g., phonetic attributes) or does it code phonemes (i.e., mental values)? To state the latter is to say that Cued Speech presents a structural aspect of a given language: phonemes. This notion is at least indirectly addressed by the current study. To conclude the former, however, is to propose that Cued Speech represents the distinctive articulatory features of speech. A fundamental purpose of the present study is to determine whether cued messages are products of a different set of distinctive features than are spoken messages.

Many discussions about cueing are conducted with the perspective that Cued Speech is a speechreading supplement: “Cues are added to the natural mouth movements of speech” (Daisey, 1987, p.17); “[Cued Speech] is a phonemically-based hand supplement to speechreading” (Caldwell, 1994, p. 58); “[Cued Speech is] a system for support of speechreading” (Cornett, 1967, p. 6); “In English [Cued Speech] utilizes eight hand shapes, placed in four different locations near the face, to supplement what is seen on the mouth” (Cornett & Daisey, 2001, p. 17). Common to these discussions is the idea that “what is seen on the mouth” is not discrete in and of itself. However, such discussions seem to overlook the idea that the hand shapes and hand placements of Cued Speech also are not discrete in and of themselves. According to Cornett, “Phonemes alike on the mouth are different on the hand, and vice versa” (Beaupré, 1984, p. iv). A paraphrase of “and vice versa” might read: ‘Phonemes alike on the hand are different on the mouth.’ Thus, it would seem that Cued Speech is no more a system for supplementing speechreading than it is a system for supplementing hand shape and hand placement reading. Because information found on the mouth in the course of cueing is assumed to be processed by the deaf native cuer as a distinctive feature of speech, one question addressed by the current study is with regard to the nature of “what is seen on the mouth.” Specifically, if speaking and cueing are presented simultaneously, does a deaf native cuer process the information on the mouth as part of the articulatory system known as speech, or does a deaf native cuer utilize “what is seen on the mouth” as a feature of a different articulatory system?

It is interesting to note that one assumption entailed in the “supplement to speechreading” perspective is that the ability to speak is requisite of the person who is cueing. In other words, without the ability to speak, the cuer cannot, by definition, produce speech information for the message receiver to “read.” If the information presented is not the product of speech, then it cannot accurately be said that the message processed by the receiver is even in part a product of “speechreading.”

It is also interesting to note that if the quality of a cuer’s speech production impacts the quality of cued messages, hearing native speakers who cue would more likely be competent cuers than would deaf native cuers. This counterintutive notion is supported by longstanding speech-based definitions and descriptions of Cued Speech.

Since its invention, various definitions and descriptions of Cued Speech have included reference to speech, speechreading, and/or sound. Even the name of the system suggests that speech production is fundamental to the integrity of cued messages. In fact, the National Cued Speech Association’s (NCSA) Board of Directors states “Reference to Cued Speech should never be made in such a way as to imply that the process of cueing equates with C[ued] S[peech]. In other words, CS in its complete form includes both cueing and speaking” (National Cued Speech Association Board of Directors, 1994, p.69). (Although not underlined in the adopted wording, references to speech, speechreading, and/or sound have been underlined in order to highlight them.)

In defining Cued Speech, the NCSA Board of Directors makes the following assertions:

A definition of Cued Speech, in order to describe it accurately and to distinguish it from all other systems developed for the benefit of hearing-impaired persons, must include at least the three basic ideas in the following statement: Cued Speech is a communication system which (1) utilizes hand configurations (eight in English) in locations (four in English) near the mouth, (2) to supplement the normal visual manifestations of speech (3) in such a way as to render the spoken language clear through vision alone ” (National Cued Speech Association Board of Directors, 1994, p.70).

The website of the National Cued Speech Association puts forth the following description: “Cued Speech is a sound-based visual communication system which, in English, uses eight hand shapes in four different locations (‘cues’) in combination with the natural mouth movements of speech, to make all the sounds of spoken language look different.” (Retrieved March 16, 2002 from http://www.cuedspeech.org)

It is unclear whether these definitions are written in terms of what hearing native English speakers think they are conveying when they cue or whether the definitions are written in terms of what it is thought that deaf native English cuers are receiving. Nevertheless, if it is found that a cued English message can differ from a spoken English message when cueing and speaking occur simultaneously, it becomes at least questionable whether speech, speechreading, and/or sound are a part of the way Cued Speech conveys information. It also brings into question whether speech, speechreading, and/or sound are an accurate part of describing how Cued Speech works.

In sum, the literature states and/or suggests that individuals who send cued messages and individuals who receive them must possess and employ knowledge of spoken language, speech production, and/or speechreading as part of the communication process. Reasons for such statements, suggestions, and assumptions might include the following rationale:

- The production and comprehension of cued information like the production and comprehension of spoken information involves use of the mouth.

- Cued phonemic referents and spoken phonemic referents can coincide with regard to their linguistic values.

- Speakers may cue while they talk and cuers may talk while they cue.

- The system itself is called “Cued Speech.”

The current study tests whether this rationale equates with the assumption that cued information entails speech sounds or renders representations of speech sounds. Perhaps it does neither. Implicit and previously untested, the aforementioned assumption has significant implications for the methodological choices and/or the conclusions that have been drawn from empirical research. This is true for studies that have examined the effect of Cued Speech on deaf children’s speech reception (such as Chilson, 1985; Clark & Ling, 1976; Kaplan, 1974; Ling & Clark, 1975; Neef, 1979; Nicholls-Musgrove, 1985; Perrier, Charlier, Hage, & Alegría, 1987; Sneed, 1972; Nicholls, 1979; Nicholls & Ling 1982; Quenin 1992), those that have focused on how cueing affects deaf children’s speech production (including Ryalls, Auger, & Hage 1994), and those that have studied cueing as it relates to language acquisition (such as Cornett, 1973; Mohay, 1983; Nash, 1973; Mosley, Williams-Scott, & Anthony, 1991; Kipila, 1985; Metzger,

1994).3

Regarding speech production in cuers, Ryalls et al. (1994) examine some phonetic attributes of speech in an effort to determine how they might be manifest in the spoken utterances of deaf cuers who use speech as a means of communication. This study is one of the first and few to examine the question of whether the phonological effects of cueing also have phonetic implications for speech production. Their research question is based on the notion that “Cued Speech does succeed in delivering more complete information on speech contrasts” (Ryalls, et al., 1994, p. 8). They raise the question of the relationship between phonological input and output, addressing whether the cued input that affects “speech reception” also improves speech production. Specifically, they examined voice onset time, syllable duration, and fundamental frequency in the speech of deaf cuers as compared with deaf non-cuers and hearing children.

Ryalls, et al. (1994) found statistically significant differences only between the non-cuers and the hearing groups. The cueing group clearly matched neither the non-cuers nor the hearing group, but fell between the two. The authors suggest that additional data, particularly with older cuers, is warranted by their study.

In light of the current study, it is significant that Ryals, et al. (1994) implicitly assume as part of their conclusions that access to cued messages (a) provides deaf cuers exposure to the phonetic attributes of speech (acoustic information rather than visible articulatory information from the cueing) and (b) that the speech of a deaf cuer is the product of such exposure. For example, Ryalls et al. (1994) say it is “obvious that a better internal concept of voiced and voiceless phonemes would naturally lead to a better distinction in production” (p. 16). However, the authors (a) do not distinguish between the deaf cuer’s knowledge of phonemic and phonetic values, (b) do not explain how the visible attributes of cueing provide for a better internal concept of an acoustically manifest feature, and (c) do not control for the influence of speech therapy on knowledge of phonetic aspects of speech production.

The implicit assumption that cueing entails and subsequently conveys features of speech production does not allow for the possibility that the visible articulators used when cueing (i.e., hand shape, hand placement, and mouth formation) might in fact produce their own set of distinctive features. In other words, such an assumption discounts the possibility that a visibly accessible phonetic distinction between the phonemes /k/ and /g/ for deaf cuers might be the presence or absence of the thumb extension [+ thumb] rather than presence or absence of voicing (Fleetwood & Metzger, 1998). It is simply an extension of this assumption for previous studies to conclude that demonstrating positive relationships between the reception of a cued language and phonological awareness relevant to literacy skills equates with demonstrating knowledge of and/or skills with the distinctive features of speech.

Ryalls et al.’s (1994) study is actually founded on assumptions made in earlier studies of cuers. For example, Nicholls (1979) and Nicholls and Ling (1982) studied the speech reception abilities of 18 profoundly deaf children under the following conditions: audition; lipreading; audition plus lipreading; cues; audition plus cues; lipreading plus cues; and audition, lipreading, plus cues. Nicholls (1979) and Nicholls and Ling (1982) found that in the lipreading plus cues condition as well as in the audition, lipreading, plus cues condition participants scored over 95% for key words in sentences and over 80% with syllables.

An underlying premise of these studies is that they are testing participants’ ability to “receive speech under seven conditions of presentation” (Nicholls & Ling, 1982, p. 265). “Cues plus lips” is characterized as one condition of speech presentation. In that condition, Nicholls (1979), and Nicholls and Ling (1982) find no statistically significant difference between the reception of linguistic information with or without audition. Subsequently, the authors conclude that “a strong correlation exists between speech perception, speech production, and linguistic skills” (Nicholls, 1979, p. 83) and that participants “receive highly accurate information on the speech signal” (Nicholls & Ling, 1982, p. 268)

In light of these conclusions, it is significant that the authors did not attempt to dissociate linguistic information in the acoustic and visible modes. In other words, the opportunity to distinguish between the features that constitute speech perception and/or production and those that constitute linguistic values and linguistic processing is not provided by the experimental design. Because the values rendered simultaneously in each modality coincided linguistically, the authors’ conclusion that “simultaneous use of two modalities enhances speech reception” (Nicholls, 1979, p. 83) actually rests on their implicit and untested assumption that cues plus lips are received and processed as a condition of speech.

In another study, Quenin (1992) finds a positive correlation between Cued Speech and the tracking performance of deaf college students who cue. “Results indicated that the reception of connected speech was considerably more efficient with cues than without” (Quenin, 1992, p. 82). In this study, three deaf cuers were exposed to the speech and speech plus cues of different speakers reading texts of two different complexities (6th -grade and 10th -grade passages, as calculated by at least five common estimation methods for determining reading level). Although there was some variance across participants and over time, all three participants did perform better in the cued conditions than in the uncued conditions, for both levels of text.

In Quenin’s study, the linguistic value of a given test item was established in deference to information found in the acoustic mode. Quenin applies the term “connected speech” to the information generated in that mode. She also applies the term to the visible by-products of the articulation of speech.

By design, participants did not access information via the acoustic mode, “remov[ing] their hearing aids in all conditions so that speech was received visually only” (Quenin, 1992, p. 54). Participants assigned linguistic value to the information that they received. The linguistic values identified by participants in the cued condition coincided with the linguistic value of test items generated in the acoustic mode.

This is evidence that the acoustic mode and the visual mode can carry information of coinciding linguistic value. However, Quenin subsequently concludes that participants are using cues as enhancements to the visible products of speech production (e.g., connected speech). In this regard, Quenin has actually tested for one thing — coinciding linguistic value — and concluded another — entailed articulatory value. Thus, evidence about one condition is used to assert an untested prima facie claim. Determining whether the former need derive from the latter tests the integrity of this claim and is fundamental to the current study.

What are the implications of this prima facie claim? Quenin’s conclusion relies on an implicit assumption for which she neither tests nor controls. Specifically, in Quenin’s study, the visible articulatory by-products of connected speech were never accompanied by cues (i.e., hand shapes and hand placements) that might result in responses linguistically different from those prompted solely by acoustic information resulting from “connected speech.” In other words, Quenin does not segregate cueing and speaking in either an articulatory sense or a linguistic one. Had she done so and had linguistic values differed along modal lines, perhaps Quenin would not have found evidence that cues support connected speech. Instead, perhaps she would have found evidence of connected cueing. At least she would have had the opportunity to determine whether connected speech and connected cueing are complete and segregated types of connected discourse.

Each of the aforementioned studies is an example of research that reflects implicit and significant assumptions about the relationship between cued information and spoken information. Each makes the assumption (a) that the processing of visual, cued input is inherently integrated with the processing of acoustic, spoken utterances, (b) that Cued Speech is perceived as supplementary to an existing articulatory system (i.e., speech) rather than that Cued Speech functions as an articulatory system in and of itself, and (c) that information on the hand (i.e., “cues”) functions as a feature of one set of articulators while information on the mouth functions as a feature of another (i.e., speech).

When describing the nature of a cued message, the aforementioned studies also do not differentiate the role of residual or aided hearing as supplementary, redundant, or as simply co-occurring. For example, Nicholls (1979) and Nicholls and Ling (1982) point out that the ceiling effects in their study between the two conditions, lipreading plus cues with audition, and lipreading plus cues without audition, prevent them from drawing any conclusions regarding the significance of the auditory signal when cueing. They point out that both profoundly deaf and hard of hearing individuals find themselves in situations where noise level and/or distance prevent the use of residual or aided hearing. That is, they make the point that it is visual information, rather than acoustic information, that is critical to both deaf and hard of hearing people. They suggest that future research test the question of the relationship between the acoustic and visual signals.

The studies mentioned above provide evidence that native users of cued English receive and perceive the same linguistic information when exposed to the same cued English utterances. Some of these studies also affirm that native users of spoken English receive and perceive the same linguistic information when exposed to the same spoken English utterances. Group- consistent responses suggest that the articulatory input that each group receives is systematic. That is, deaf cuers who participated in the studies perceive the phonemic, morphemic, and syntactic information that constitutes their particular cued language (e.g., American English, Australian English, Mandarin Chinese). Some questions that have not been tested are: While each cued language utilizes a system of phonemic referents (i.e., allophones), do these referents entail either the phonetic features or the allophones of the counterpart spoken language (e.g., American English, Australian English, Mandarin Chinese)? Are cued allophones characterized by a different bundle of features than are spoken allophones targeting the same phonemes? These questions drive the current study.

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to determine whether Cued Speech entails speech. By the design of Cued Speech, the mouth is employed in the production of cued allophones. The mouth is also employed in the production of spoken allophones. Perhaps this fact that cueing and speaking employ the mouth in the production of allophones (phonemic referents) is what feeds the prevailing assumption that cueing employs and/or conveys speech. No doubt, bolstering this assumption are findings that deaf native cuers of a language recall the same linguistic information as hearing native speakers of a language when both are exposed to simultaneously cued and spoken information. A question that has not been tested is to what degree, if any, are the features of speech production required of and responsible for coinciding linguistic values simultaneously produced in the spoken (acoustic) and cued (visible) modes.

Even if information on the mouth of a deaf native cuer and the mouth of a hearing native speaker coincides, linguistically relevant contrast can still exist with regard to the simultaneous production of cued and spoken phonemic referents (allophones). That is, although it probably never occurs intentionally in natural interaction, one can employ the hand shapes and hand placements necessary to produce the cued English word talk and simultaneously employ the voice, manner of articulation, and place of articulation that produce the spoken English word dog. For each word, simultaneously cued and spoken, the mouth shapes would coincide. By presenting deaf and hearing participants with this type of linguistically dissociated stimuli, one could examine the assumption that the distinctive features that define the articulation of speech are somehow entailed in the production and reception of cued information.

Cueing one linguistic message while speaking another is not general practice among the members of cueing communities. Nevertheless, experimentally providing this type of stimuli allows an opportunity to determine the salient features of cueing and, subsequently, the relationship, if any, between Cued Speech and speech. Findings have both theoretical and practical implications in the areas of language development, phonological awareness, and literacy development. Potentially, findings of the current study impact the interpretation of some previous findings, characterizations, and descriptions related to Cued Speech.

Theoretically, the ways in which systems of communication are processed by human beings is of interest to psychologists and linguists, and to those investigating communication and speech perception. Practically, gaining a better understanding of the relationship between Cued Speech use and spoken language knowledge can provide useful information regarding who is a viable candidate for using a cued language, whether or not a cuer must have some measure of hearing or some prior knowledge of a language, and ultimately, how cued languages might be applied in bilingual or multilingual contexts, educational curriculums, literacy learning, speech therapy, and other settings. For these reasons, the question presented for investigation is, ‘Does Cued Speech entail speech?’

Methods

Participants

Twenty-six participants were included in this study. Thirteen were prelingually deaf, sighted4 native5 cuers of American English, including 8 females and 5 males ranging between 16 and 30 years of age. The mean age at which these deaf individuals began using English in the cued mode is 4:4. A hearing control group consisted of 13 hearing, sighted native speakers of American English, including 7 females, and 6 males between the ages of 18 and 32. The mean age at which these hearing individuals began speaking English is 0:8. All hearing participants reported that speaking was the primary mode and English the primary language used by their parents and in school.

Of the deaf participants, 10 reported profound losses, 1 reported a severe to profound loss, and 2 reported severe losses. Ten indicated that they were deaf at birth. Three reported that onset of deafness occurred prior to age 18 months. Ten deaf participants indicated that they received English via the cued mode prior to age 3. Two indicated that their initial exposure to cued English was age 5. One participant reported first exposure to cued English beginning at age 8. Twelve deaf participants reported that initial exposure to English via the cued mode was from at least one parent. One reported initial exposure at school, followed by cueing from at least one parent at home. In the educational setting, cueing was the primary mode and English the primary language beginning in preschool for 10 participants, starting in first grade for 2 participants, and beginning in fourth grade for 1 participant.

In order to better control for the effects of access to both cued and spoken information, hearing native speakers who had no knowledge of cueing were chosen as the control group; while they could fully access the cued information, they had not developed the ability to process it. For the purposes of the current study, this condition is considered analogous to that of deaf native cuers who might have some experience with sound, but who do not have the acoustic acuity by which the spoken information would be sufficiently accessible to them acoustically. Hence, they would not have the opportunity to process the spoken information. The hearing control group consisted of 13 hearing, sighted native speakers of American English, including 7 females, and 6 males between the ages of 18 and 32. The mean age at which these hearing individuals began speaking English is 0:8.

Test Material

In order to address the relevant study question a videotape was produced. By design, videotaped material contained both linguistically dissociated and linguistically associated stimuli conveyed via simultaneously cued and spoken test items. Specifically, the videotape contained both cued and spoken representations of isolated phonemes, isolated words, and short phrases. These stimuli were presented in two different conditions: (a) the associated condition, in which the cued and spoken messages coincided linguistically, and (b) the dissociated condition, in which the cued and spoken messages did not coincide linguistically.

For both conditions, and because each of cueing and speaking utilize the mouth toward the rendering of linguistic information, test items were chosen such that the mouth could be simultaneously employed in the rendering of both visible (cued) and acoustic (spoken) information (e.g., spoken talk and cued dog). Test items were selected with the goal that 50% of the simultaneously cued and spoken information not coincide linguistically (designated as the N test items) and that 50% of said information would coincide linguistically (designated as the C test items).

Participants were provided two trials in each condition, although they were not aware of this. In their first trial, deaf participants were provided visible, cued (i.e., hand shapes, hand placements, and mouth shapes) messages only. In their first trial, a hearing control group was provided acoustic (i.e. sounds of speech) messages only. In the second trial both the deaf and the hearing participants were provided both the cued and the spoken messages (i.e., both the visual and acoustic modes). As directed by written instruction, participants used written English to record the information that they received from the stimuli. A hearing control group native to spoken English was provided the same two conditions.

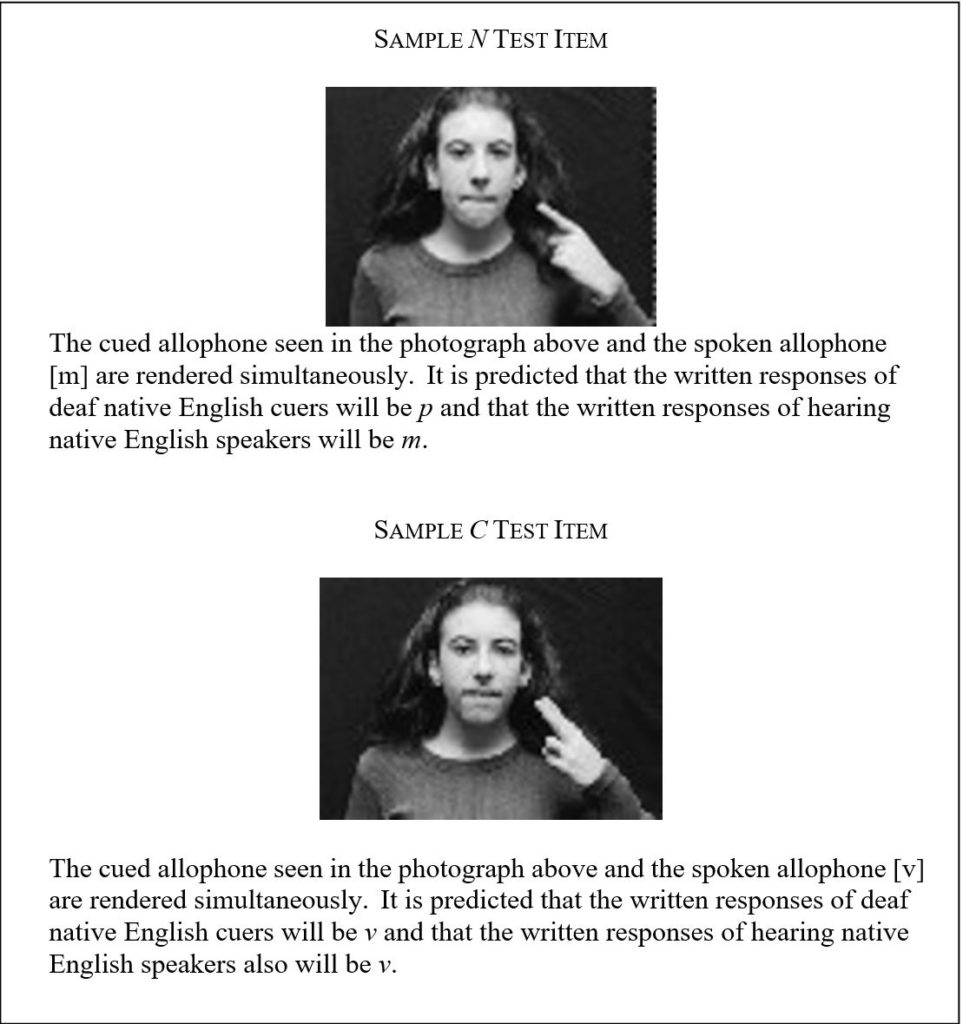

For each test item, it is predicted that the hearing control group will respond in keeping with values ascribed to acoustic distinctive features produced by speaking, as described by example below. For each test item, it is predicted that the group of deaf cuers will respond irrespective of speech production or speech products. Those responses will instead reflect values ascribed to distinctive features produced by cueing, also described by example below.

The design of the current study provides for cross-modal linguistic dissociation while maintaining mode-internal production constraints. So, in terms of how cued allophones and spoken allophones are produced, mouth shape coincides across modes for co-presented test items. Thus, test stimuli are never dissociated mode-internally. Theoretically, this allows a cued allophone of /p/ and a spoken allophone of /m/ to co-occur. Mouth shape should not cause any unexpected responses from the hearing group since mouth shape coincides with the production of both the spoken and the cued utterances. The hand cues themselves should be meaningless to participants in the hearing control group, since none of them knows a cued language or even Cued Speech.

By design of the current study, it is hypothesized that a given N test item will elicit, for example, the written response p from each of the deaf native English cuers and the written response m from each of the hearing native English speakers (see figure 1). This prediction is based on how allophones are rendered via cueing and how they are rendered via speaking. For example, where the value /p/ is represented in the cued mode, the visible allophone consists of a hand shape that, by itself, represents any of /d/,/p/, /zÍ/ a simultaneously produced mouth shape that, by itself, represents any of /m/, /b/, /p/. Resulting from the intersection of the specific hand shape and mouth shape is a discrete visible symbol that serves to discriminate among these five possibilities. That visible symbol is a cued allophone of /p/ (see Figure 1). By design of the current study, an acoustic symbol yielding a spoken allophone of /m/ is co-presented in the spoken mode as a bilabial, voiced, nasal, continuant.

Also by design of the current study, it is predicted that a given C test item will elicit, for example, the written response v from all respondents in both groups of participants. Like the N test items, this prediction is based on the manner in which allophones are rendered via cueing and via speaking. For example, where the value /v/ is represented in the cued mode, the visible allophone consists of a specific hand shape that, by itself, represents any of /k/, /v/, /∂/, or /z/ and a simultaneously produced specific mouth shape that, by itself, represents either /v/ or /f/. Resulting from the intersection of the specific hand shape and mouth shape is a discrete visible symbol that serves to discriminate among these five possibilities. That visible symbol is a cued allophone of /v/ (see Figure 1). By design of the current study, an acoustic symbol yielding a spoken allophone of /v/ is co-presented in the spoken mode as a labiodental, voiced, fricative.

For the N test items, where a cued allophone of /p/ and a spoken allophone of /m/ are co-presented, a written response of m would indicate that the products of speech are primary or overriding where decision making about linguistic values is concerned. If the written response p were recorded, this would serve as evidence that the features and products of speech are not relevant to linguistic decision making.

The C test items do not allow for this distinction. For example, where a cued allophone of /v/ and a spoken allophone of /v/ are co-presented, a written response of v by the deaf participants would not serve as evidence that the features and/or products of speech production are relevant to them. This is because recognizing a cued allophone of /v/ is predicted as sufficient for providing a written response of v. Previous research has only tested this condition in which the linguistic value of messages rendered in both modes is intended to be the same.

For both the N and the C test items, it is predicted that the hearing control group will respond in keeping with values ascribed to a bundle of acoustic features produced by speaking, irrespective of cuem production or cuem products. For each test item it is predicted that the group of deaf cuers will respond in keeping with values ascribed a bundle of visible features produced by cueing, irrespective of speech production or speech products.

The issue of the participants’ visual and acoustic access to the test items is central to the validity of the current study. As pointed out by numerous researchers, audio-visual information may share a common metric (Summerfield, 1987; Schwartz et al., 1998), and anyone receiving access to both heard and seen information may fuse the two (see, for example, McGurk, & MacDonald, 1976). Any data collected without controlling for visual and acoustic access would leave as ambiguous any conclusion regarding whether the distinctive features of cueing and the distinctive features of speaking differ or are one and the same. Thus, unless the test participants are provided access to both the cued (visible) and the spoken (acoustic) test items, the current study cannot effectively distinguish between whether responses are the result of attributes of the articulatory system accessed by the participants or whether the responses are simply the products of accessibility constraints.

Controlling for access has implications with regard to several study-related questions including: (a) Do the distinctive features of speech (i.e., voice, manner, and place) constitute or are they part of the articulatory system (i.e., Cued Speech) through which deaf native cuers send and receive linguistic information? (b) When provided the opportunity to simultaneously access cued and spoken information, do deaf native cuers defer to the products of an articulatory system not defined by the distinctive features of speech? (c) If an articulatory system other than speech drives the linguistic perceptions of deaf native cuers, are these decisions so driven even when speech is co-presented? The current study directly addresses question (a) above. However, in light of questions (b) and (c), the validity of the study’s findings is dependent on controlling for the participants’ access to the test items.

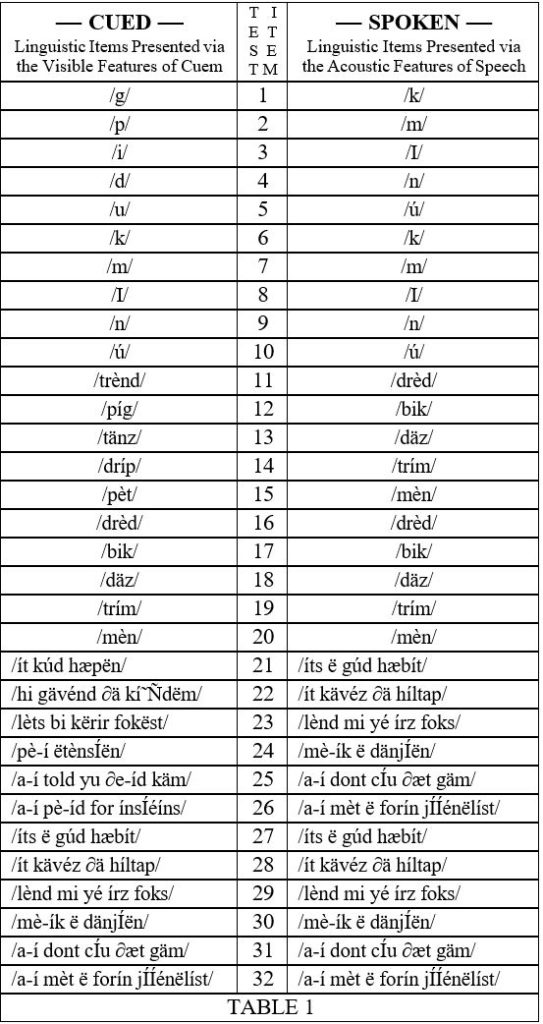

Items appearing in the list of Cued test items were co-presented with items appearing in the list of Spoken test items. For example, Cued test item #3 and Spoken test item #3 were simultaneously rendered (see Table 1). Cued test items were selected strictly with regard for their visible attributes (e.g., hand shape, mouth shape). Spoken test items were selected strictly with regard for their acoustic attributes (e.g., +

voice). Both the N test items and the C test items were selected with regard for these considerations. All test items matched in terms of mouth shape, regardless of whether they coincided linguistically. The stimuli were divided according to both length and condition. That is, the progression of stimuli moved from representation of isolated phonemes to isolated words and then to phrases. In each of these groupings the first five were N test items followed by five C test items. Test items were presented in the sequence shown in Table 1. All participants provided written responses.

1 Cued Speech has most commonly been described as a system of communication that is both visible and acoustic in nature. It was first described by Fleetwood and Metzger as a visible articulatory system (Fleetwood & Metzger, 1991). See Fleetwood and Metzger 1998 for an in depth discussion of Cued Speech as a visible articulatory system.

2 cued language: (noun) a class of consonant-vowel languages rendered via the employent of articulators, including non-manual signals (found on the mouth), hand shapes, and hand placements (i.e., cuem), that are modulated in conjunction with other non-manual information, such as head and eyebrow movements, to convey phonemic, (or tonemic), morphemic, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information in the visible medium; a member of this class of languages.

3 These studies have been reviewed in detail in previous editions of this journal. See, for example, Leybaert & Charlier, 1996; LaSasso & Metzger, 1998).

4 For purposes of the current study, it is assumed that sighted, hearing native speakers have seen the mouth movements that accompany speech. Consequently, sighted, hearing people have the opportunity to formulate relationships between a mouth shape that is seen and a speech sound that is heard. In contrast, and for the purpose of this experiment, it is assumed that by virtue of being deaf, sighted deaf individuals do not access the sounds of speech with the same degree of acuity as do hearing individuals. Thus, while sighted deaf native cuers have experience 1) seeing mouth shapes as one aspect of a cued message and 2) seeing the mouth shapes used in the production of spoken messages, they do not have the opportunities afforded sighted hearing individuals with regard to formulating relationships between a mouth shape that is seen and a speech sound that is heard. This distinction between sighted deaf and sighted hearing individuals is a fundamental consideration in determining at least some of the criteria that governed the determination of eligible participants.

5 For purposes of the current study, the term native is defined in consideration of (a) language (e.g., English), (b) mode (e.g., cued or spoken), (c) number of years exposed to a given mode and language, and (d) cultural/community involvement.

The deaf participants for this study all had been cueing American English since their early years at school, and for at least half of their lives. Hearing individuals who began using English in the spoken mode no later than their early years at school and who has used spoken English for more than half of his/her life is also considered native for this study. The mean age at which the hearing individuals began using English in the spoken mode is 0:8.

Consideration of language and mode is clearly necessary for this study, since it focuses on the accessibility of each. Consideration of cultural and community involvement is emphasized by Roy (1986). She found that a variety of language experts, including linguists, sociolinguists, and anthropologists, agree that language users one might define as native (those whose performance is viable for research purposes) are typically those individuals who interact within a community of users. Thus, the fourth criteria was that participants be active members in the deaf cueing community, as evidenced by interaction with other cuers in the home, socially, and at community events such as family cue camps.